The best that most of us can hope to achieve in physics is simply to misunderstand at a deeper level.

This project was inspired by Daniel Schiffman’s Youtube video on the subject, viewable here.

Spring forces are perhaps the most fun physical interaction to play with in a simulation. Even better, they are very simply described by a short equation, known as Hooke’s Law.

where is the spring force, is the displacement of the length of the spring from its rest length (where it’s neither being pulled or compressed), and is a constant unique to each spring, representing its stiffness.

This should make intuitive sense - the more you compress a spring, the more it seems to push back to expand to its rest length.

This basic relationship is all we need to simulate a spring. Once we know the direction that it is being pulled or pushed in, we can apply the force in the opposite direction.

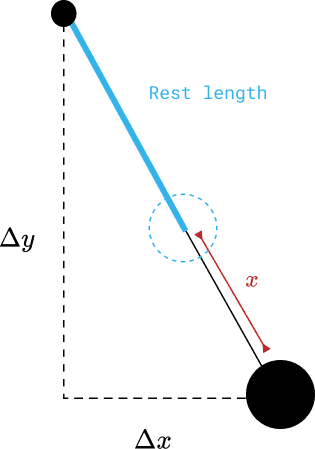

The displacement value from our equation can now be seen to be the spring length minus the rest length. The current spring length, can be found from the displacements in the and directions according to the Pythagorean theorem.

In figure 1, a setup of our spring is shown extended from its rest length. We will therefore apply the force back up towards the anchor point, opposite of the direction the ball is being pulled. We can create a vector to hold the displacement components of the ball.

We have the magnitude of the force to apply to the ball from Hooke’s Law. To apply it in the right direction, we can normalize (scale it to a magnitude of one), then multiply each component by the magnitude of the force to give us the force vector for both and components.

Once the force is found, Newton’s second law tells us that . However, since I only have one type of spring in this simulation, it’s simple to just give each spring unit mass and skip this step.

I also added some gravity to the component of the acceleration. We can now change the velocity by the acceleration, using Euler integration in the same way as previous projects.

Before updating the position, though, we can simulate air resistance and friction in the spring by multiplying the velocity by something like , meaning it will get progressively smaller every timestep. Without this, it would keep bouncing forever. We can now update the position of our ball and draw everything accordingly.

As an extension, I created classes for both the spring and the ball and made an array for each. The spring takes in two balls, one at each end, allowing a whole chain of them to be put together!